When an employer passes you over for a promotion in favor of someone decades younger, tells you you’re “overqualified” during an interview, or suggests you should consider retirement, the question of legal protection naturally arises. The Age Discrimination in Employment Act—commonly known as the ADEA—is the federal law that makes these actions illegal. Understanding what the ADEA covers, who it protects, and how it works is the first step toward determining whether you have a valid claim.

This article explains the ADEA’s core protections and practical requirements while comparing federal law to the often stronger protections available under Pennsylvania and New Jersey state statutes.

What Is the Age Discrimination in Employment Act?

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act is a federal statute that prohibits employment discrimination against individuals who are 40 years of age or older. Congress enacted the law in 1967 to address the pervasive workplace bias that prevented older workers from obtaining and retaining employment based on stereotypes about age rather than actual ability.

The Purpose Behind the ADEA

Congress found that older workers faced systematic disadvantages in hiring, promotion, and retention. Employers routinely set arbitrary age limits unrelated to job performance. The ADEA was designed to promote employment of older persons based on ability rather than age, to prohibit arbitrary age discrimination, and to help employers and workers address problems arising from the impact of age on employment.

How the Law Has Evolved

Since 1967, the ADEA has been amended several times to expand its reach. The law now covers state and local government employers regardless of their size, following the Supreme Court’s decision in Mount Lemmon Fire District v. Guido, 586 U.S. 1 (2018). The Older Workers Benefit Protection Act of 1990 added specific requirements for waivers of ADEA claims in severance agreements.

Current Enforcement Activity

Age discrimination remains a significant workplace problem. According to EEOC Enforcement and Litigation Statistics (2025), workers filed 16,223 age discrimination charges with the EEOC in fiscal year 2024. This represents a 41% increase from fiscal year 2022, when 11,500 charges were filed. The surge in filings reflects both the growing older worker population and increased awareness of age-based workplace bias.

Who Does the ADEA Protect?

The ADEA’s protections are more limited than many workers realize. The law establishes specific thresholds for both the age of protected workers and the size of covered employers.

The Age Threshold

The ADEA protects individuals who are 40 years of age or older from employment discrimination. This threshold has remained unchanged since the law’s enactment. Notably, the Supreme Court clarified in O’Connor v. Consolidated Coin Caterers Corp., 517 U.S. 308 (1996), that the ADEA does not prohibit an employer from favoring an older worker over a younger one, even if both are over 40. The law targets discrimination against older workers, not protection of any particular age group.

The protected population continues to grow. According to BLS Employment Projections (2025), 38.8 million workers age 55 and older now participate in the U.S. labor force, comprising 23.1% of all workers. This demographic reality means age discrimination affects a substantial and increasing portion of the workforce.

Which Employers Are Covered

The ADEA applies to private employers with 20 or more employees. It also covers employment agencies, labor organizations with 25 or more members, and state and local governments regardless of employee count. Federal employees have separate protections under a different section of the statute.

Employers must have met the 20-employee threshold for each working day in 20 or more calendar weeks during the current or preceding year. Courts count all employees, including part-time workers, toward this threshold.

Who Falls Outside ADEA Protection

Several categories of workers cannot bring ADEA claims. Employees of businesses with fewer than 20 workers have no federal age discrimination remedy, though state laws may provide coverage. Independent contractors are not protected under the ADEA. The law also exempts elected officials, their personal staff, and bona fide executives entitled to retirement benefits of $44,000 or more annually upon reaching age 65 (29 U.S.C. § 631(c)).

What Workplace Conduct Does the ADEA Prohibit?

The ADEA makes it unlawful for covered employers to discriminate against individuals 40 or older in any aspect of employment. The statute, codified at 29 U.S.C. § 623(a), broadly prohibits age-based discrimination in hiring, firing, compensation, and all terms and conditions of employment.

Discrimination in Hiring and Firing

Termination remains the most common allegation in age discrimination cases. According to the EEOC’s report on the State of Age Discrimination (2018), 55% of ADEA charges alleged discriminatory discharge, up from 45% in 1992. The law prohibits employers from making employment decisions based on age stereotypes or assumptions about older workers’ abilities.

The ADEA prohibits employers from taking any of the following actions based on a worker’s age:

- Refusing to hire a qualified applicant because of assumptions that older workers are less adaptable, less technologically capable, or likely to retire soon

- Terminating an older worker while retaining younger employees with equal or lesser qualifications

- Selecting older workers disproportionately for layoffs or reductions in force

- Using neutral-sounding criteria like “overqualified” or “too much experience” as proxies for age in hiring decisions

- Forcing older workers into early retirement through pressure, threats, or intolerable working conditions

- Setting maximum age limits for hiring or mandatory retirement ages (with narrow exceptions)

Discrimination in Promotions and Compensation

The ADEA prohibits age discrimination in promotions, compensation, job assignments, and training opportunities. According to EEOC data (2018), 25% of ADEA charges alleged discrimination in terms or conditions of employment—nearly double the percentage from 1992. This includes denying older workers raises, bonuses, or beneficial assignments available to younger colleagues.

Age-Based Harassment

Harassment based on age can create a hostile work environment that violates the ADEA. According to the EEOC (2018), 21% of ADEA charges alleged age-based harassment in 2017—more than triple the 6% rate in 1992. Comments like “dinosaur,” “over the hill,” and “too old to learn new tricks,” when severe or pervasive enough to alter working conditions, can support a hostile work environment claim.

How Do Workers Prove Age Discrimination Under the ADEA?

Proving age discrimination requires meeting a specific legal standard that differs from other federal employment laws. The Supreme Court established this standard in Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc., 557 U.S. 167 (2009), fundamentally shaping how ADEA claims are analyzed.

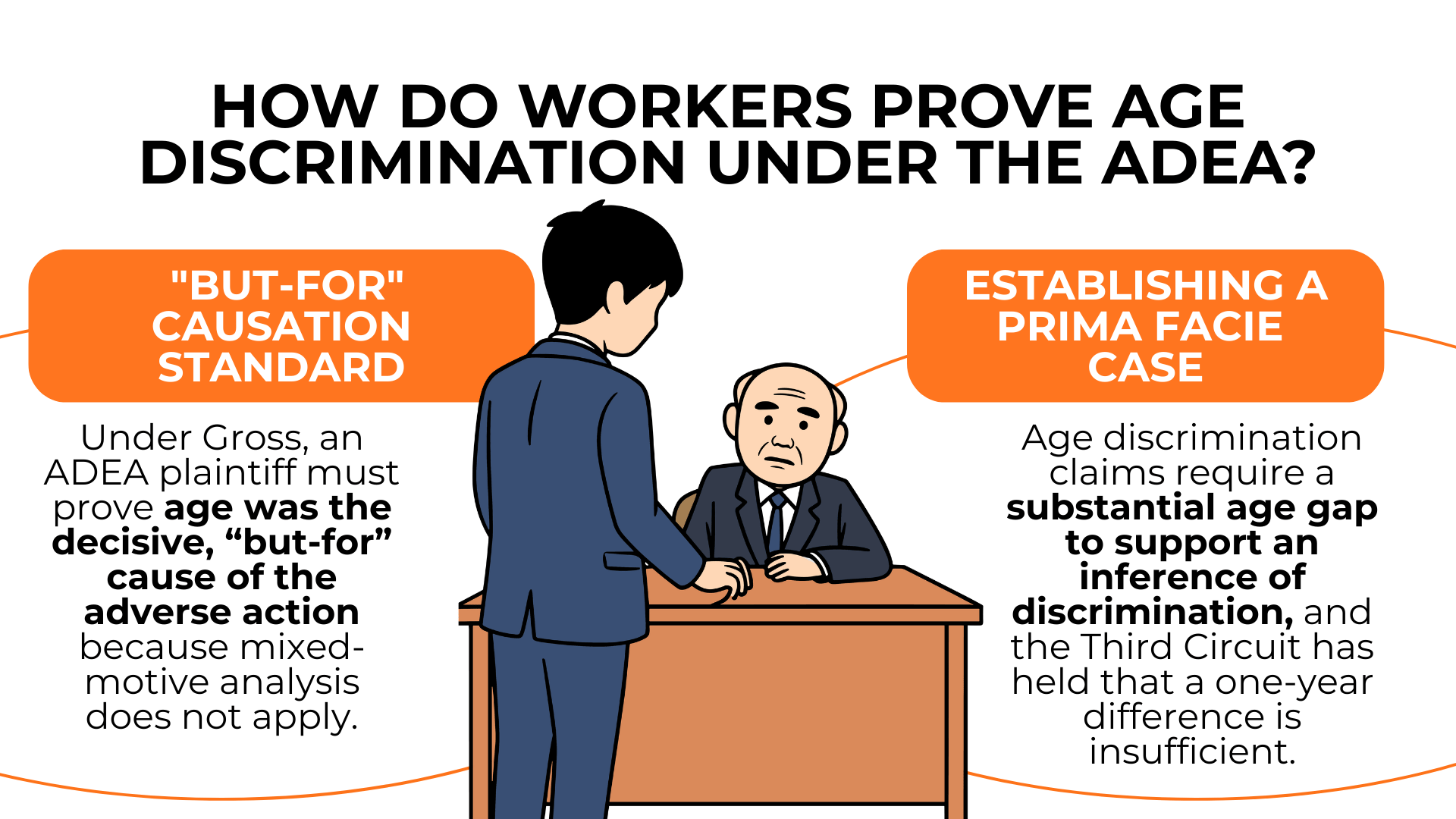

The “But-For” Causation Standard

Under Gross, a plaintiff must prove that age was the “but-for” cause of the adverse employment action. This means demonstrating that the employer would not have taken the challenged action but for the employee’s age. Age must be THE reason, not merely A reason among several factors.

This standard is more demanding than Title VII’s “motivating factor” test. The Supreme Court specifically held that the mixed-motive framework—where discrimination need only be one motivating factor—does not apply to ADEA claims. Workers must build their cases around proving age was the decisive factor from the outset.

Establishing a Prima Facie Case

Most age discrimination cases proceed under the burden-shifting framework established in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973). To establish a prima facie case, a plaintiff must show: (1) membership in the protected class (age 40 or older); (2) qualification for the position; (3) an adverse employment action; and (4) circumstances giving rise to an inference of discrimination.

For the fourth element, courts typically look at whether the plaintiff was replaced by or treated less favorably than someone “substantially younger.” The Third Circuit requires a substantial age gap without applying a bright-line rule, examining the totality of circumstances. In Baron v. Abbott Laboratories, 672 Fed. Appx. 158 (3d Cir. 2016), the court found that a one-year age gap was insufficient to support an inference of discrimination.

The Role of Circumstantial Evidence

Direct evidence of age discrimination—explicit statements linking age to the employment decision—is rare. Most cases rely on circumstantial evidence such as age-related comments by decision-makers, statistical patterns in hiring or terminations, inconsistent treatment compared to younger employees, or shifting explanations for the employer’s actions.

Once a plaintiff establishes a prima facie case, the burden shifts to the employer to articulate a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for its action. If the employer does so, the plaintiff must prove that reason is pretextual and that age discrimination was the true cause.

What Are the Deadlines for Filing an ADEA Claim?

Strict filing deadlines apply to ADEA claims, and missing these deadlines can permanently forfeit your rights. The administrative exhaustion requirements under 29 U.S.C. § 626(d) must be satisfied before any federal lawsuit can proceed.

Filing with the EEOC

Before filing a lawsuit under the ADEA, workers must first file a charge of discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Pennsylvania and New Jersey are both “deferral states” because they have state agencies (the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission and New Jersey Division on Civil Rights) that enforce state age discrimination laws. In deferral states, workers have 300 days from the discriminatory act to file their EEOC charge.

Workers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey must observe these filing deadlines:

- 300 days from the discriminatory act to file an EEOC charge for federal ADEA claims

- 180 days from the discriminatory act to file with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission for state PHRA claims

- 180 days from the discriminatory act to file with the New Jersey Division on Civil Rights (though filing directly in court within 2 years is also permitted)

- 90 days from receipt of the EEOC’s right-to-sue notice to file a federal lawsuit

The Waiting Period Before Lawsuit

Unlike Title VII, the ADEA permits workers to file a lawsuit 60 days after submitting their EEOC charge, even without receiving a right-to-sue letter. Alternatively, workers may wait for the EEOC to complete its investigation and issue a Notice of Dismissal or Right to Sue. If the EEOC issues such a notice, the worker must file suit within 90 days of receipt. Courts enforce this 90-day deadline strictly.

Why Timing Matters

The importance of these deadlines cannot be overstated. According to EEOC data (2023-2024), the average EEOC charge takes 11 months to investigate and resolve. Workers who miss the initial filing deadline lose their federal claims entirely, regardless of how strong the underlying evidence of discrimination might be.

What Damages Can Workers Recover Under the ADEA?

The ADEA provides remedies designed to make victims whole, but these remedies are more limited than those available under state laws. Understanding what you can and cannot recover is essential to evaluating the strength of a potential claim.

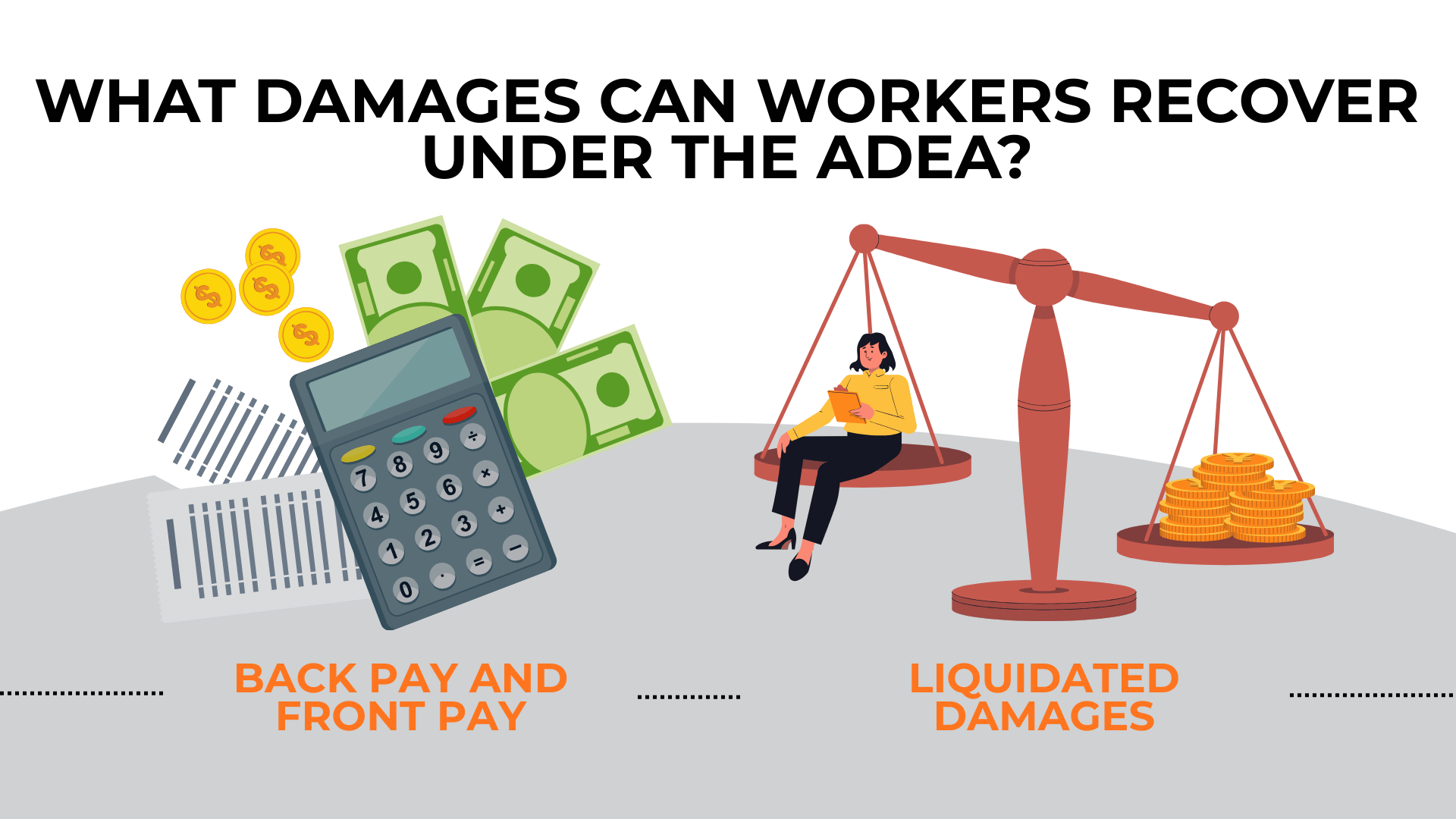

Back Pay and Front Pay

The primary ADEA remedy is back pay—the wages and benefits the worker would have earned from the date of discrimination to the date of judgment. Courts calculate back pay based on the worker’s salary, bonuses, commissions, and the value of lost benefits. Front pay may be awarded in lieu of reinstatement when returning to the job is not feasible due to hostility, the position no longer exists, or other circumstances make reinstatement impractical.

The EEOC achieved significant recoveries for discrimination victims. According to the EEOC Annual Performance Report (2025), the agency secured nearly $700 million for over 21,000 victims of employment discrimination in fiscal year 2024—the highest total recovery in the agency’s recent history. Of this amount, EEOC litigation data (2025) shows $3.18 million was recovered specifically through ADEA lawsuits.

Liquidated Damages for Willful Violations

When an employer’s violation is “willful”—meaning the employer knew or showed reckless disregard for whether its conduct violated the ADEA—the court may award liquidated damages equal to the back pay award, effectively doubling the recovery. The Supreme Court defined this standard in Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Thurston, 469 U.S. 111 (1985). The jury determines whether the violation was willful.

What the ADEA Does Not Provide

Unlike Title VII and most state discrimination laws, the ADEA does not permit recovery of compensatory damages for emotional distress or punitive damages. This significant limitation means that workers who suffered severe emotional harm from discrimination cannot recover for that injury under federal law. The damages are limited to economic losses and, where applicable, the liquidated damages multiplier.

How Do Pennsylvania and New Jersey Laws Compare to the ADEA?

State employment discrimination laws often provide stronger protections than the federal ADEA. Workers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey may have claims under both federal and state law, and choosing the right statute can significantly affect the outcome of a case.

New Jersey Law Against Discrimination Advantages

New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination (N.J.S.A. 10:5-1 et seq.) is one of the most employee-friendly anti-discrimination statutes in the country. Courts interpret the LAD liberally as remedial legislation.

New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination provides several advantages over the federal ADEA:

- Protects workers as young as 18 from age discrimination, not just those 40 and older (Bergen Commercial Bank v. Sisler, 157 N.J. 188 (1999))

- Covers all employers regardless of size, with no minimum employee threshold

- Permits uncapped compensatory damages for emotional distress and punitive damages for especially egregious conduct

- Requires no administrative exhaustion—workers may file directly in Superior Court within the 2-year statute of limitations

- Allows attorney fee enhancement of 20-35% in typical cases, up to 100% in exceptional cases (Rendine v. Pantzer, 141 N.J. 292 (1995))

Pennsylvania Human Relations Act Protections

The Pennsylvania Human Relations Act (43 P.S. § 951 et seq.) provides protections similar to the ADEA but with some important differences. The PHRA protects workers 40 and older and covers employers with 4 or more employees—a lower threshold than the ADEA’s 20-employee requirement. This means workers at smaller businesses who have no federal remedy may still have state claims.

However, the PHRA has significant limitations. Under Hoy v. Angelone, 720 A.2d 745 (Pa. 1998), punitive damages are not available. PHRA claims in state court are tried to a judge, not a jury. Workers must file with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission within 180 days and wait one year for administrative processing before filing in court (unless the PHRC dismisses earlier).

Choosing the Right Law for Your Claim

The choice of which law to pursue depends on the specific facts of each case. For workers at employers with fewer than 20 employees, the PHRA or NJ LAD may be the only available remedy. For cases involving significant emotional distress, New Jersey’s LAD offers compensatory and punitive damages unavailable under the ADEA or PHRA. For workers who want a jury trial in Pennsylvania, filing the federal ADEA claim rather than relying solely on the PHRA preserves that right.

The economic impact of age discrimination underscores the importance of pursuing available remedies. According to AARP and The Economist Intelligence Unit (2020), age discrimination cost the U.S. economy an estimated $850 billion in GDP in 2018, with losses projected to reach $3.9 trillion annually by 2050 if current patterns persist.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does the ADEA protect workers under 40?

No. The federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act only protects workers who are 40 years of age or older. However, New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination protects workers as young as 18 from age-based discrimination, providing broader coverage than federal law.

Can I sue my employer under the ADEA if the company has fewer than 20 employees?

The ADEA only applies to employers with 20 or more employees. If your employer has fewer than 20 workers, you cannot file a federal ADEA claim. However, Pennsylvania’s Human Relations Act covers employers with just 4 or more employees, and New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination covers all employers regardless of size.

Do I have to file with the EEOC before I can sue under the ADEA?

Yes. Before filing a federal ADEA lawsuit, you must first file a charge of discrimination with the EEOC. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, you have 300 days from the discriminatory act to file this charge. You may file a lawsuit 60 days after submitting your EEOC charge.

Can I recover damages for emotional distress under the ADEA?

No. Unlike Title VII and most state laws, the ADEA does not permit recovery of compensatory damages for emotional distress or punitive damages. ADEA remedies are limited to back pay, front pay, and liquidated damages (which double the back pay award) if the violation was willful. New Jersey’s LAD does permit uncapped compensatory and punitive damages.

What does “but-for” causation mean for my ADEA claim?

Under the ADEA, you must prove that age was THE reason—not just A reason—for the adverse employment action. This means showing that but for your age, the employer would not have taken the action against you. This is a higher standard than some state laws, which may only require showing age was a “motivating” or “determinative” factor.

Protecting Your Rights Under Federal and State Law

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act provides essential protections for workers 40 and older, prohibiting age-based discrimination in hiring, firing, promotions, and all terms of employment. The 41% increase in ADEA charges since 2022 reflects both the growing older worker population and the persistence of age bias in American workplaces.

Understanding the ADEA’s requirements—including the “but-for” causation standard, the 300-day filing deadline, and the limitations on available damages—is critical for workers considering whether to pursue a claim. Equally important is recognizing that state laws in Pennsylvania and New Jersey often provide stronger protections, broader coverage, and greater remedies than federal law alone.

If you have questions about your rights under the ADEA or state age discrimination laws, contact The Lacy Employment Law Firm to discuss your situation.