When a supervisor tells an employee their promotion depends on going on a date, or threatens termination for refusing sexual advances, the law recognizes this as one of the most direct forms of workplace sexual harassment. Quid pro quo harassment involves an explicit or implicit exchange: provide sexual favors, or face consequences to your job. Pennsylvania and federal law treat these situations seriously, and when a supervisor’s demands result in actual employment consequences, employers face strict liability with no available defense.

This guide explains what quid pro quo harassment means under Pennsylvania law, what legal elements must be proven, how liability works differently than other harassment claims, and what steps you should take if you find yourself in this situation.

What Is Quid Pro Quo Harassment Under Pennsylvania Law?

The Legal Definition of Quid Pro Quo

Quid pro quo is Latin for “this for that.” In the employment context, quid pro quo harassment occurs when a supervisor or someone with authority over your job conditions employment benefits on your submission to sexual demands. The supervisor might offer something positive (a raise, promotion, favorable schedule) in exchange for sexual favors, or threaten something negative (termination, demotion, poor assignments) for refusing.

This differs from hostile work environment harassment, which involves pervasive unwelcome conduct that makes the workplace abusive. Quid pro quo focuses on a specific exchange or condition tied to job benefits. One demand coupled with adverse action can establish a quid pro quo claim, while hostile work environment claims typically require showing a pattern of conduct.

How Federal and Pennsylvania Laws Protect Workers

Both federal Title VII (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)) and the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act (43 P.S. § 955) prohibit sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination. The statutes don’t use the phrase “quid pro quo,” but courts have interpreted sex discrimination prohibitions to encompass this conduct since the Supreme Court’s decision in Meritor Savings Bank, FSB v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986).

Pennsylvania law provides broader coverage than federal law. Title VII only applies to employers with 15 or more employees, leaving workers at small businesses without federal protection. The PHRA covers employers with just 4 or more employees, meaning Pennsylvania workers at smaller companies still have state law protections. This coverage difference matters significantly for workers at small businesses, medical practices, or local companies that fall below the federal threshold.

Why These Claims Are Taken Seriously

Sexual harassment claims have increased substantially in recent years. According to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (FY 2023), more than 7,700 sexual harassment charges were filed with the EEOC in fiscal year 2023, representing a 25% increase from the prior year and the highest level in 12 years. When the EEOC takes harassment cases to litigation, outcomes strongly favor employees. The EEOC Office of General Counsel Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report documented a 97% favorable resolution rate in district court litigation.

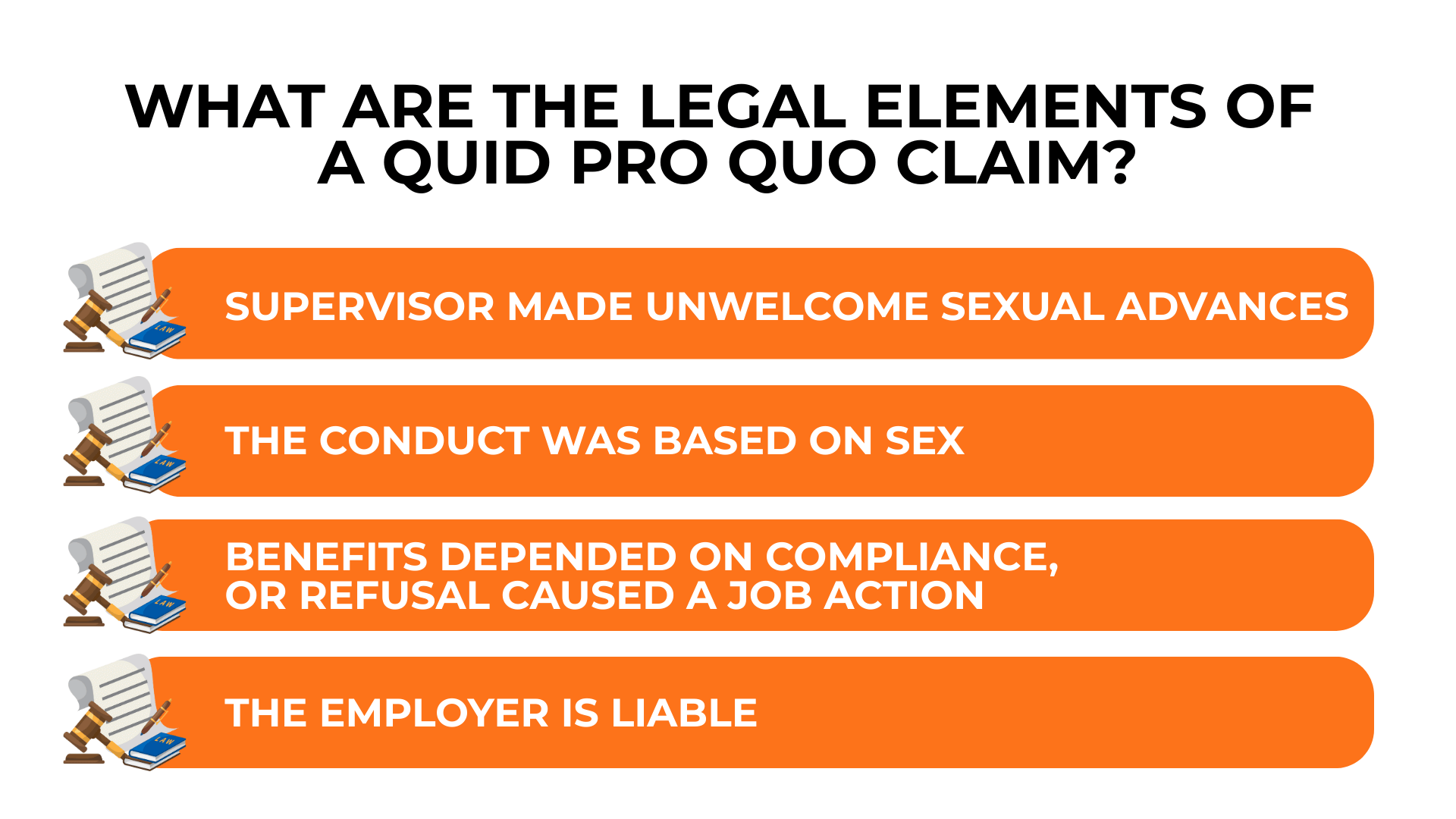

What Are the Legal Elements of a Quid Pro Quo Claim?

The Four Elements Courts Require

To establish a quid pro quo harassment claim, a plaintiff must prove specific legal elements. Courts across federal and Pennsylvania jurisdictions apply consistent standards derived from Title VII case law. The following elements must be demonstrated:

- The plaintiff was subject to unwelcome sexual advances or requests for sexual favors from a supervisor or someone with authority over employment decisions

- The harassment occurred because of the plaintiff’s sex

- Submission to the sexual conduct was an express or implied condition for receiving job benefits, or refusal resulted in a tangible employment action

- A basis exists for holding the employer liable for the supervisor’s conduct

The third element distinguishes quid pro quo from other harassment claims. There must be a direct connection between the sexual demand and an employment outcome.

What Counts as Unwelcome Conduct

The “unwelcome” requirement focuses on whether the plaintiff invited or solicited the conduct. It does not require physical resistance or verbal refusal in every instance. Conduct is unwelcome if the employee did not solicit or incite it and regarded it as undesirable or offensive.

Courts recognize that power imbalances in the workplace complicate how employees respond to supervisors’ advances. An employee who submits to sexual demands to keep their job has not welcomed the conduct. The key inquiry is whether the employee, by their conduct, indicated the advances were unwelcome, not whether they ultimately capitulated under pressure.

Understanding Tangible Employment Action

A tangible employment action is central to quid pro quo claims and triggers strict employer liability. The Supreme Court defined this concept in Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998), as “a significant change in employment status.” The following actions qualify as tangible employment actions:

- Termination or constructive discharge

- Failure to hire when the hiring decision was conditioned on sexual submission

- Denial of a promotion the employee was otherwise qualified to receive

- Demotion to a lower position or pay grade

- Reassignment with significantly different responsibilities

- A decision causing a significant change in benefits, compensation, or working conditions

When a supervisor’s quid pro quo harassment culminates in any of these outcomes, the employer faces strict liability. This means the employer cannot defend itself by pointing to anti-harassment policies or claiming ignorance of the supervisor’s conduct.

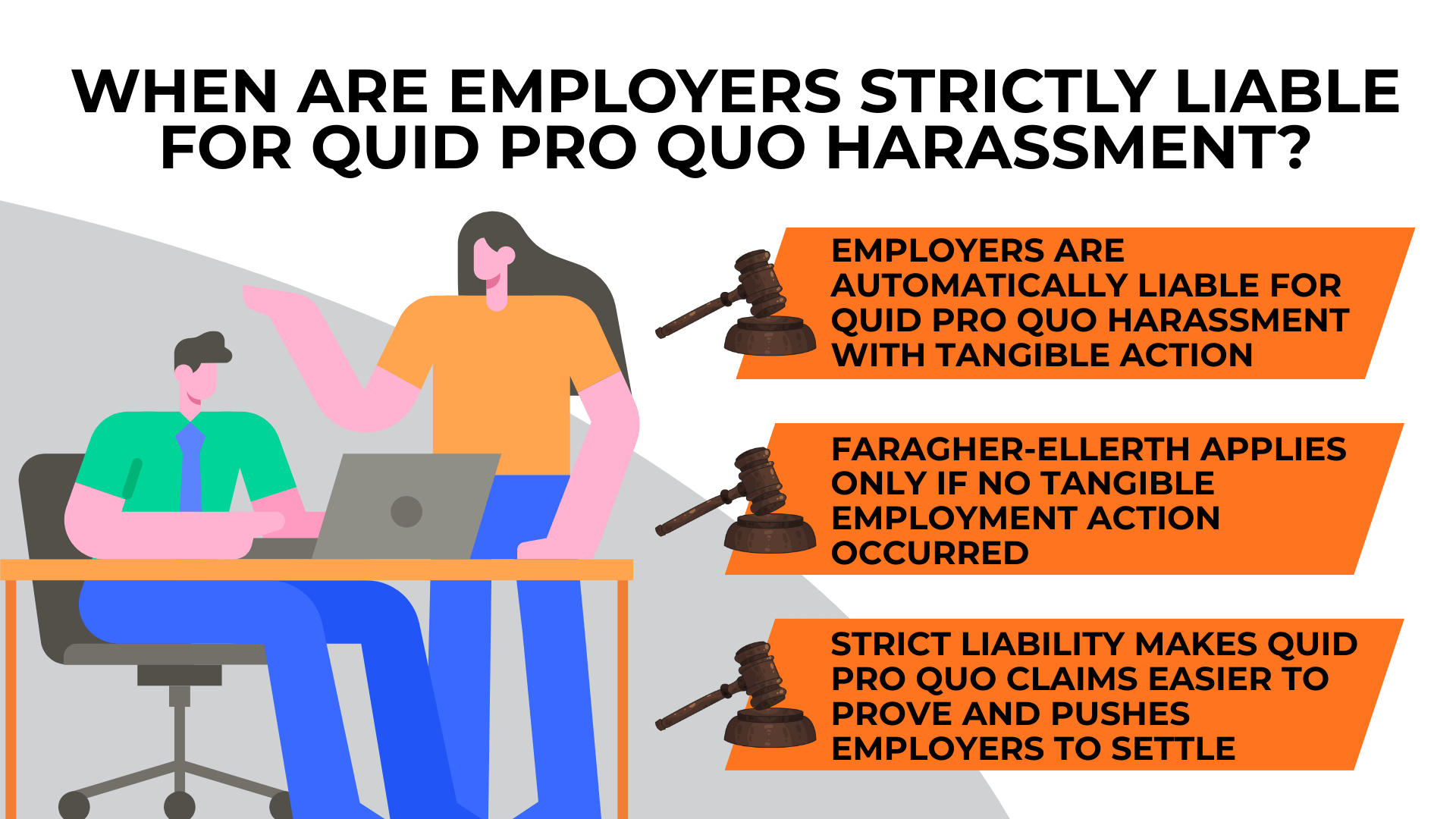

When Are Employers Strictly Liable for Quid Pro Quo Harassment?

The Strict Liability Rule Explained

The strict liability standard is what sets quid pro quo harassment apart from hostile work environment claims. When a supervisor’s harassment results in a tangible employment action—the employee is fired, demoted, denied a promotion, or suffers another significant adverse change—the employer is automatically liable.

Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998), established this rule. The Supreme Court reasoned that when a supervisor uses their authority to cause tangible harm to a subordinate, that action is necessarily aided by the agency relationship. The employer placed the supervisor in a position to make employment decisions, and the employer bears responsibility when that authority is abused.

Why the Faragher-Ellerth Defense Cannot Be Raised

In hostile work environment cases where no tangible employment action occurs, employers can raise an affirmative defense under the Faragher-Ellerth framework. This defense requires the employer to prove both that it exercised reasonable care to prevent and correct harassment, and that the employee unreasonably failed to take advantage of preventive opportunities.

However, this defense is completely unavailable when harassment results in tangible employment action. The Supreme Court explicitly limited the affirmative defense to cases without tangible employment consequences. This means an employer cannot escape liability by showing it had a harassment policy, conducted training, or offered a complaint procedure. Once the tangible action occurred, the employer is liable regardless of its prevention efforts.

The Practical Impact on Your Case

For employees, the strict liability standard significantly strengthens quid pro quo claims. The focus of litigation shifts to proving what happened—the sexual demand and the employment consequence—rather than debating whether the employer’s policies were adequate. Employers cannot argue they tried to prevent harassment or that the employee should have complained internally before the adverse action.

This also affects settlement dynamics. Employers facing strict liability often have greater incentive to resolve cases before trial because their defenses are limited. The question becomes one of damages, not liability.

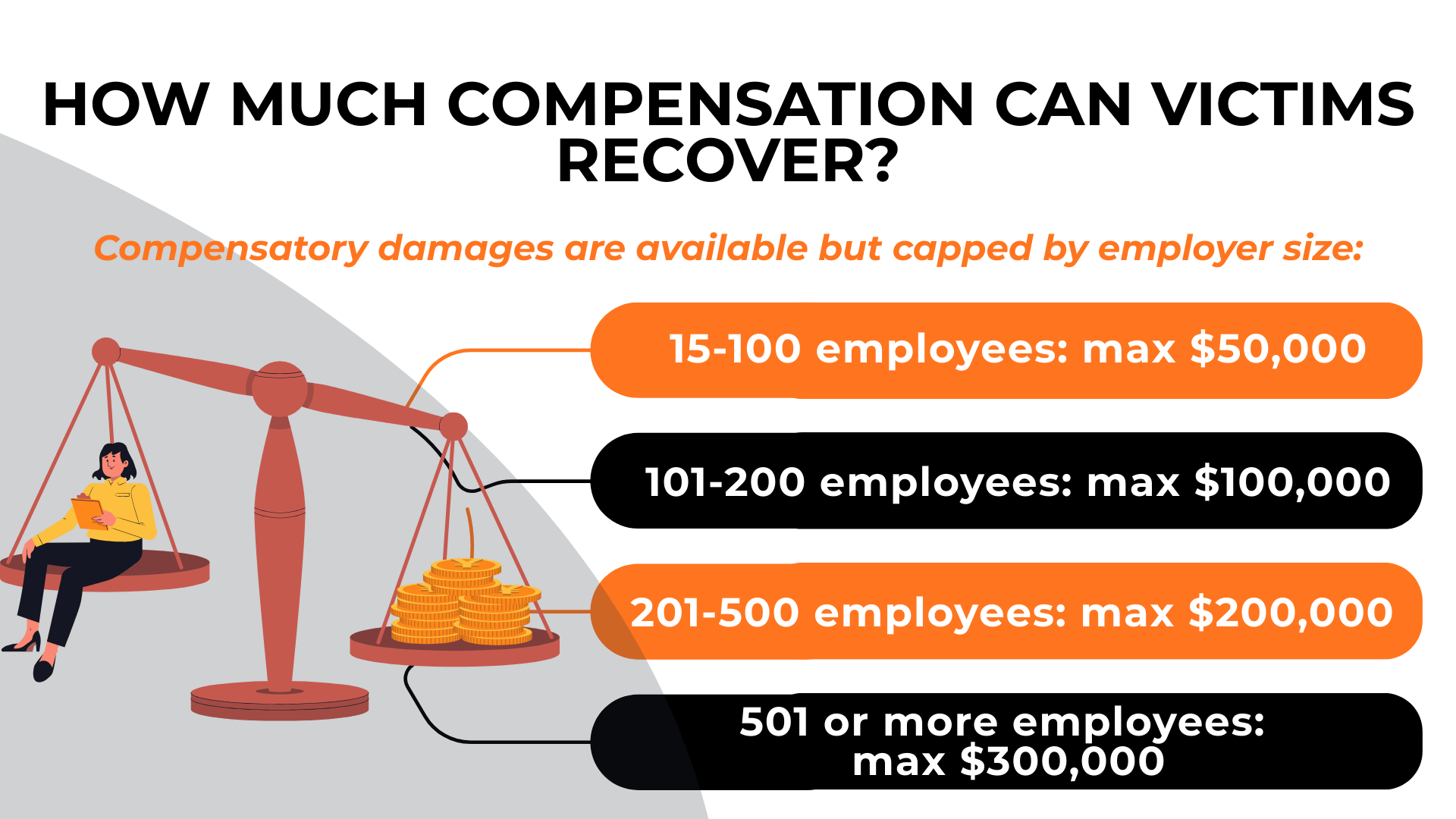

How Much Compensation Can Victims Recover?

Federal Title VII Damages

Federal law authorizes several categories of damages for quid pro quo harassment victims. Back pay compensates for wages lost from the date of the adverse action, and courts calculate this based on what the employee would have earned absent the discrimination. Front pay covers future lost earnings when reinstatement isn’t feasible, often awarded as a lump sum. Per Pollard v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 532 U.S. 843 (2001), neither back pay nor front pay is subject to statutory caps.

Compensatory damages for emotional distress, mental anguish, and other nonpecuniary harm are available but subject to caps based on employer size under 42 U.S.C. § 1981a(b)(3):

- Employers with 15-100 employees: maximum $50,000

- Employers with 101-200 employees: maximum $100,000

- Employers with 201-500 employees: maximum $200,000

- Employers with 501 or more employees: maximum $300,000

Punitive damages may also be awarded when the employer acted with malice or reckless indifference, though not against government employers.

Pennsylvania PHRA Advantages

The PHRA offers one substantial advantage: no caps on compensatory damages. Unlike federal law, Pennsylvania places no statutory limit on emotional distress damages. For cases involving significant psychological harm, this can result in substantially larger awards than federal caps would permit.

However, punitive damages are not available under the PHRA. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court confirmed this limitation in Hoy v. Angelone, 554 Pa. 134, 720 A.2d 745 (Pa. Sup. Ct. 1998). This creates a strategic tradeoff: cases with provable emotional distress may recover more under PHRA, while cases with egregious employer conduct warranting punishment may benefit from pursuing Title VII punitive damages.

Pennsylvania also permits individual liability for harassers under 43 P.S. § 955(e), which prohibits aiding, abetting, inciting, or coercing unlawful discriminatory acts. This means the supervisor who engaged in quid pro quo harassment can be sued personally under state law—a remedy unavailable under federal Title VII.

Recovery Statistics Show Substantial Awards

Data from the EEOC demonstrates significant monetary recoveries in harassment cases. According to EEOC Data Highlight No. 2 (April 2022), $299.8 million was recovered for sexual harassment claims between fiscal years 2018 and 2021, benefiting 8,147 individuals. This represented $104 million more than the prior four-year period. More broadly, the EEOC 2024 Annual Performance Report documented nearly $700 million recovered for discrimination victims in fiscal year 2024, the highest in the agency’s recent history.

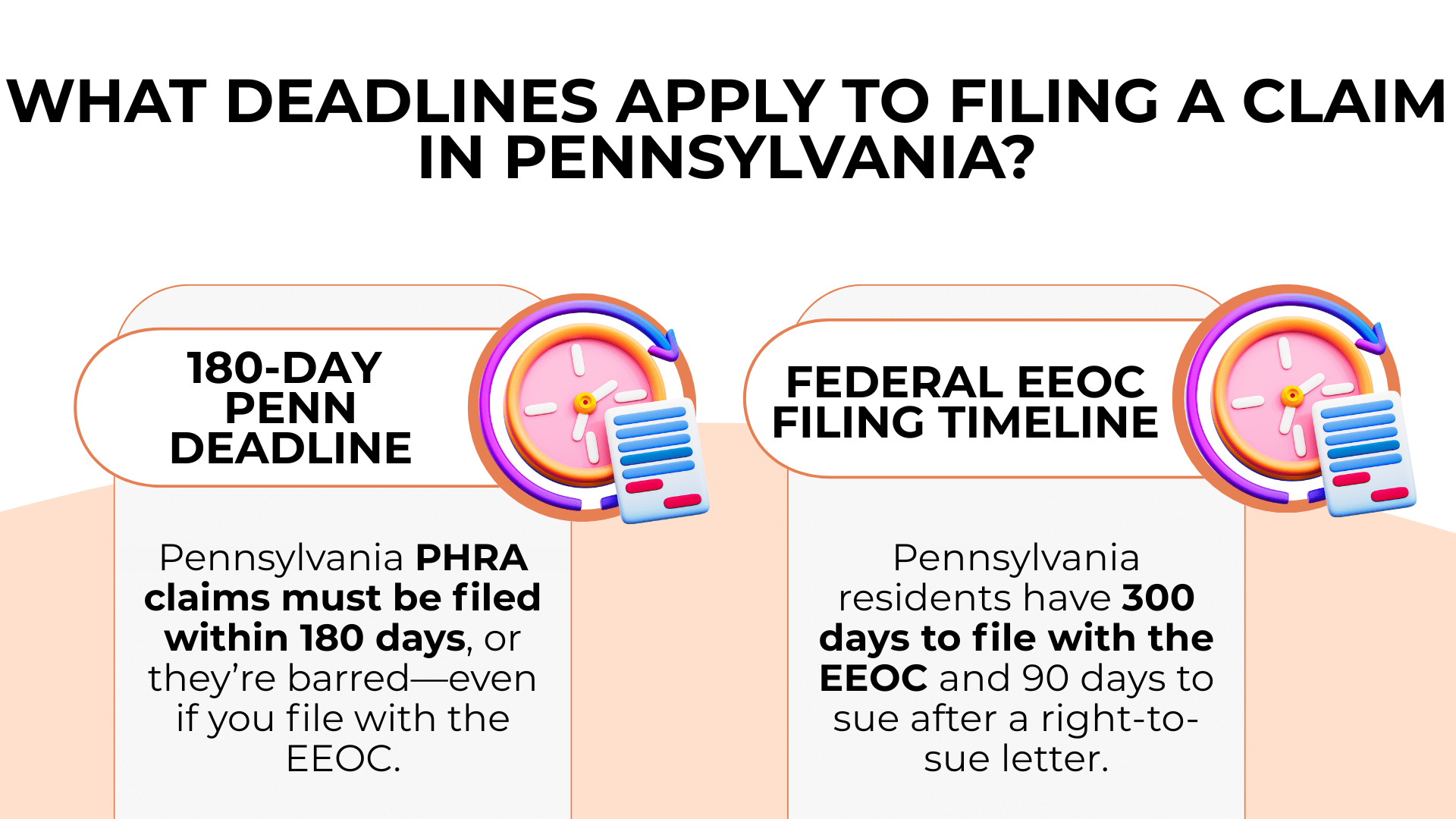

What Deadlines Apply to Filing a Claim in Pennsylvania?

The 180-Day Pennsylvania Deadline

Pennsylvania’s filing deadline is shorter than many employees realize. Under 43 P.S. § 959(h), complaints to the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission must be filed within 180 days of the discriminatory act. This is approximately six months from the date of the quid pro quo harassment or resulting adverse employment action.

Missing this deadline forfeits your state law claims entirely. Even if you file a federal EEOC charge within the federal deadline, you cannot pursue PHRA claims if the 180-day window has closed. Given the PHRA’s advantages—uncapped damages and individual harasser liability—this deadline is critical to preserve.

Federal EEOC Filing Timeline

Federal law provides Pennsylvania residents with 300 days to file a charge with the EEOC because Pennsylvania is a “deferral state” with its own enforcement agency. After filing, the EEOC investigates the charge. You can request a right-to-sue letter after 180 days if the investigation remains incomplete.

Once you receive the right-to-sue letter, you have exactly 90 days to file a lawsuit in federal court. This deadline is strictly enforced. Courts routinely dismiss cases filed even one day late.

Why Filing Early Preserves All Options

Filing within 180 days preserves claims under both federal and state law. This gives you maximum flexibility in deciding which forum to pursue and which remedies to seek. After filing with the PHRC, the agency maintains exclusive jurisdiction for one year before you can file in state court. If the PHRC closes your complaint, you have two years to file in Pennsylvania’s Court of Common Pleas.

Many employees delay while hoping the situation improves or second-guessing whether they have a valid claim. These delays can cost you valuable legal rights. Consulting an attorney early allows you to understand your options while all deadlines remain intact.

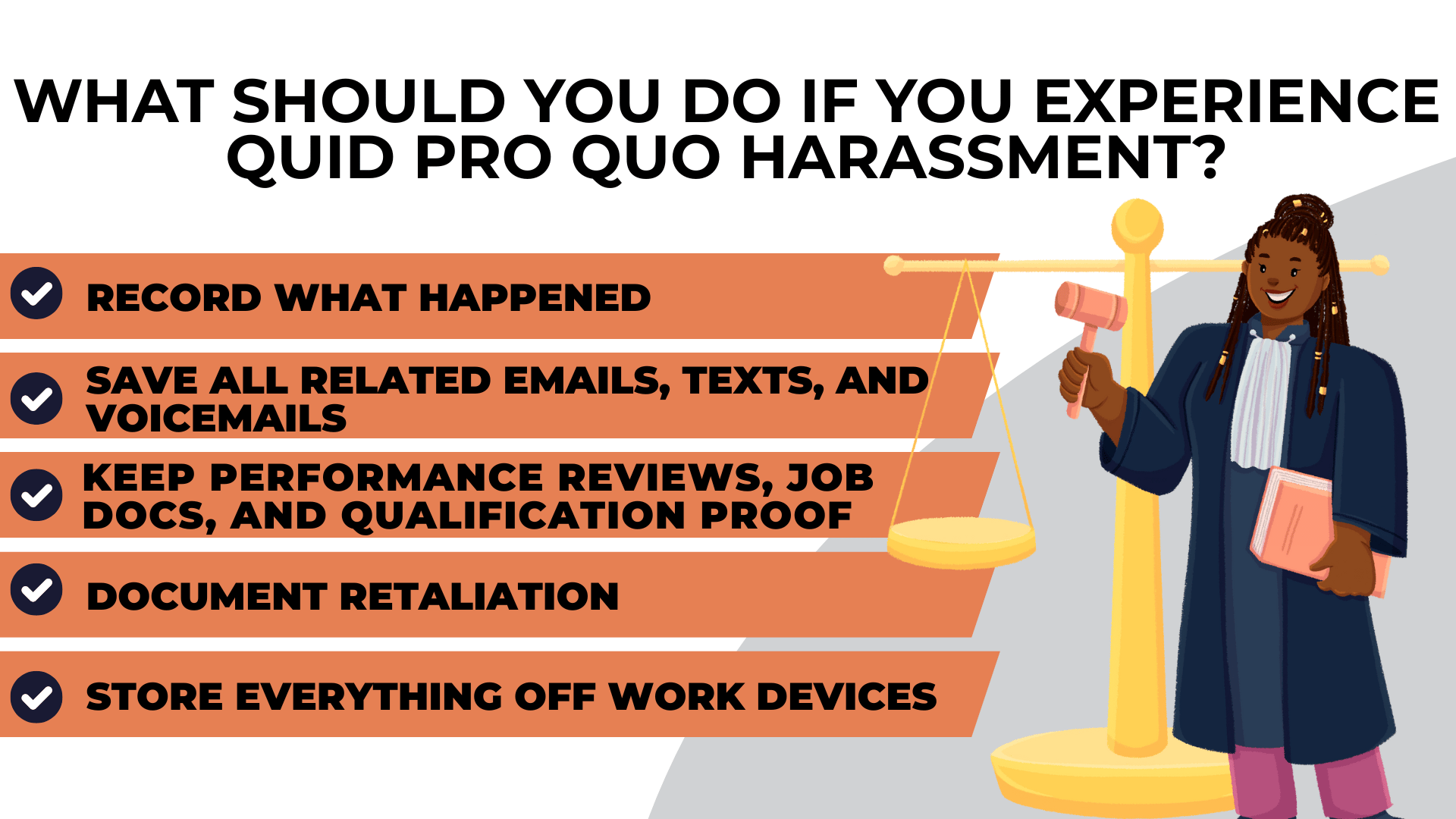

What Should You Do If You Experience Quid Pro Quo Harassment?

Document Everything Immediately

Documentation created close in time to events carries significant weight in legal proceedings. You should begin keeping detailed records as soon as harassment occurs, even before deciding whether to pursue legal action. Focus on the following documentation priorities:

- Write down exactly what was said or done, including the date, time, location, and any witnesses present

- Preserve all electronic communications including emails, text messages, and voicemails related to the harassment or your job status

- Save copies of performance reviews, job descriptions, and any documents showing your qualifications for positions denied to you

- Note changes in how you’re treated after refusing advances or making complaints, including differences in assignments, schedule, or supervisor interactions

- Keep records outside your work computer or email, which you may lose access to if terminated

Creating these records doesn’t commit you to any particular course of action, but it preserves evidence that may become crucial if you decide to pursue a claim.

Understand Why Most Victims Don’t Report

If you’re hesitant about taking formal action, you’re not alone. According to the EEOC Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace (2016), approximately 90% of individuals who experience workplace harassment never file a formal charge. Concerns about retaliation, disbelief, damage to careers, and the emotional toll of the process all contribute to underreporting.

The prevalence of harassment itself is striking. The same EEOC study found that between 25% and 85% of women report experiencing workplace sexual harassment, depending on how surveys define harassment. When surveys ask about specific behaviors rather than using legal terminology, approximately 60% of women report experiencing harassment. EEOC data from fiscal years 2018-2021 shows that women filed 78.2% of sexual harassment charges, though men filed 21.8%, confirming that harassment affects workers of all genders.

Consult an Attorney Before Internal Complaints

Before reporting harassment through internal company channels, consider consulting an employment attorney. Understanding your legal rights before speaking with HR allows you to make informed decisions about timing and approach. HR departments serve the company’s interests, which may not align with yours.

An attorney can explain what evidence strengthens your position, what statements to avoid, and how internal complaints affect your legal options. Early consultation also ensures you don’t inadvertently miss filing deadlines while navigating internal processes.

Frequently Asked Questions About Quid Pro Quo Harassment

Can I sue my supervisor personally for quid pro quo harassment?

Under Pennsylvania’s PHRA, yes. The statute at 43 P.S. § 955(e) prohibits any person from aiding, abetting, inciting, or coercing unlawful discriminatory practices. Courts have interpreted this to permit individual liability against supervisors who engage in harassment. Federal Title VII does not provide this option—only the employer entity can be held liable under federal law. Pursuing both the employer and the individual harasser may increase your potential recovery and your leverage in settlement negotiations.

What if my employer has fewer than 15 employees?

Pennsylvania law still protects you. While federal Title VII only applies to employers with 15 or more employees, the PHRA covers employers with 4 or more employees. This means workers at small businesses, medical practices, and local companies have state law remedies even when federal law doesn’t apply. The PHRA’s uncapped compensatory damages and individual liability provisions remain available regardless of employer size, as long as the employer has at least 4 employees.

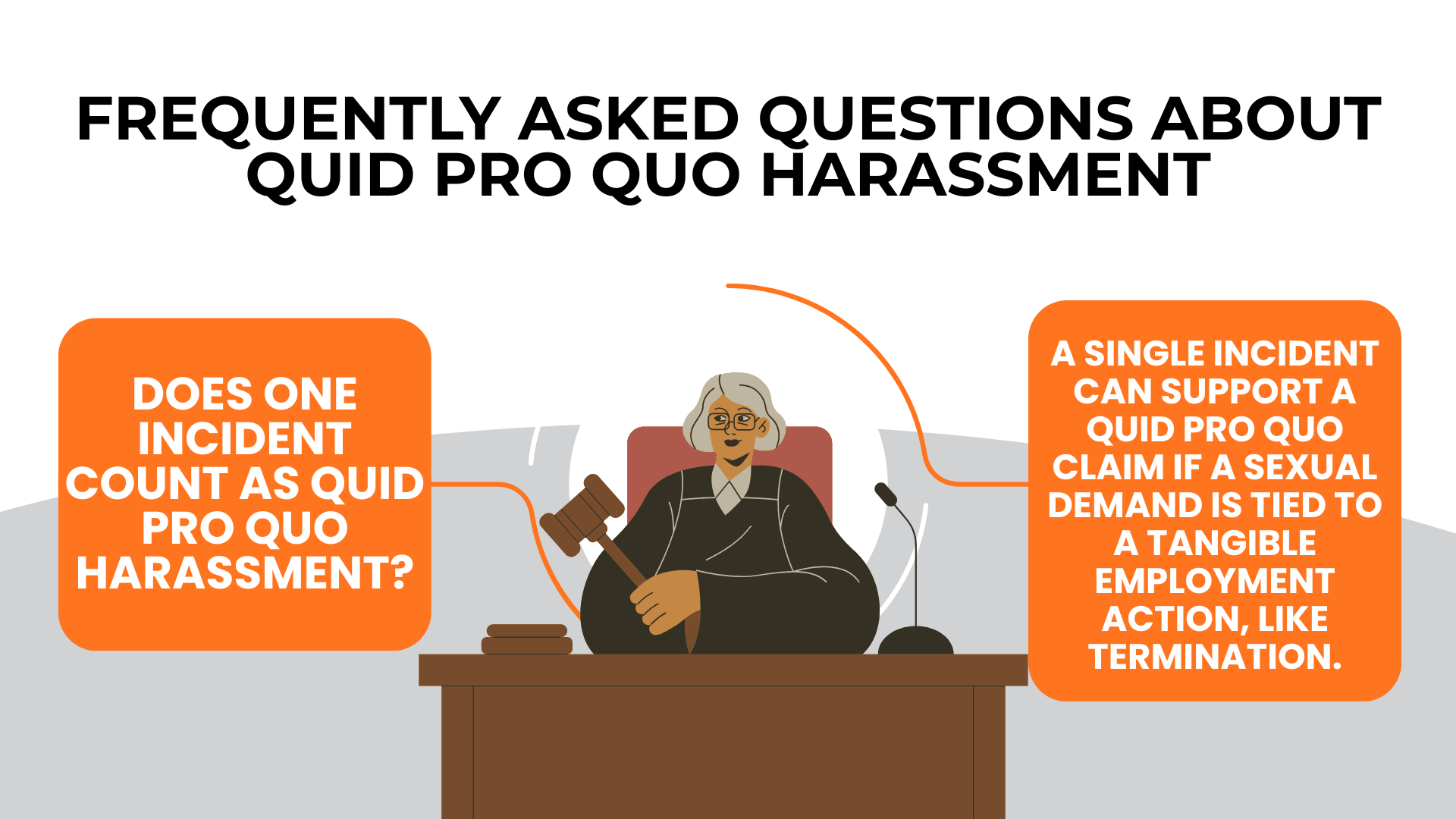

Does one incident count as quid pro quo harassment?

Yes, a single incident can establish a quid pro quo claim if it involves a tangible employment action. Unlike hostile work environment claims, which typically require showing a pattern of severe or pervasive conduct, quid pro quo harassment focuses on the connection between a sexual demand and an employment consequence. If a supervisor demands sexual favors and fires you for refusing, that single exchange supports a claim—there’s no requirement to prove repeated harassment.

What if I submitted to the demands to keep my job?

Submitting to a supervisor’s sexual demands does not bar you from bringing a claim. The legal question is whether the conduct was unwelcome—whether you invited or solicited it and whether you regarded it as desirable. Courts recognize that employees sometimes comply with demands under economic coercion, fearing termination or other consequences. Coerced submission is still harassment. What matters is that you did not welcome the sexual conduct, regardless of whether you ultimately capitulated to preserve your employment.

How long do quid pro quo harassment cases typically take?

Timeline varies significantly depending on whether cases settle or proceed to trial. After filing with the PHRC, the agency has exclusive jurisdiction for one year. Many cases resolve during this administrative phase or through settlement negotiations that follow. Federal cases may move faster after obtaining a right-to-sue letter, though federal court litigation can take one to three years depending on the court’s docket and case complexity. An attorney can provide case-specific estimates based on your circumstances and goals.

Protecting Your Rights Under Pennsylvania Law

Quid pro quo harassment represents an abuse of workplace authority that both federal and Pennsylvania law treat as serious sex discrimination. When supervisors condition employment benefits on sexual submission or punish employees for refusing, employers face strict liability—they cannot escape responsibility by pointing to policies or training.

Pennsylvania law offers meaningful advantages for harassment victims, including coverage of smaller employers with just 4 employees, uncapped compensatory damages, and the ability to sue individual harassers personally. However, these protections come with a critical deadline: 180 days to file a complaint with the PHRC, which is shorter than the federal 300-day window.

Taking action requires understanding both what the law prohibits and the practical steps to protect your claim. Documenting harassment, preserving evidence, and consulting with an attorney while deadlines remain intact can make the difference between a strong case and missed opportunities.

If you have questions about a potential quid pro quo harassment claim, contact The Lacy Employment Law Firm to discuss your situation.